On the 21st May 1707 the Confederate forces received reinforcements and a new general, the Prussian Wilhelm von Pritzwalk. He immediately set about organising his forces for a flank march to turn the French position at Rheineck. Leaving a Brigade to spread out in front of the French lines and ordering them to light extra campfires at night, he constructed pontoons northeast of Rheineck and crossed the rest of his force to the right bank of the Frank river. His plan was to march down this bank and bridge the river again behind the French position. It called for speed and guile, and the wily Prussian had both. He set up the new pontoons on the early morning of the 26th May. French piquets had spotted dust clouds on the northern bank, and Fois-Gras immediately realised the situation. Ever aggressive, his immediate thought was to defeat the weak screening force that must be holding the Allied position opposite his lines. Then he decided that time was against him and concentrated his forces for a withdrawal.

Meanwhile, the first elements of the Allied forces were crossing the Frank in a hurried fashion. The scene was set for a battle where reserves would arrive piecemeal and advance into battle.

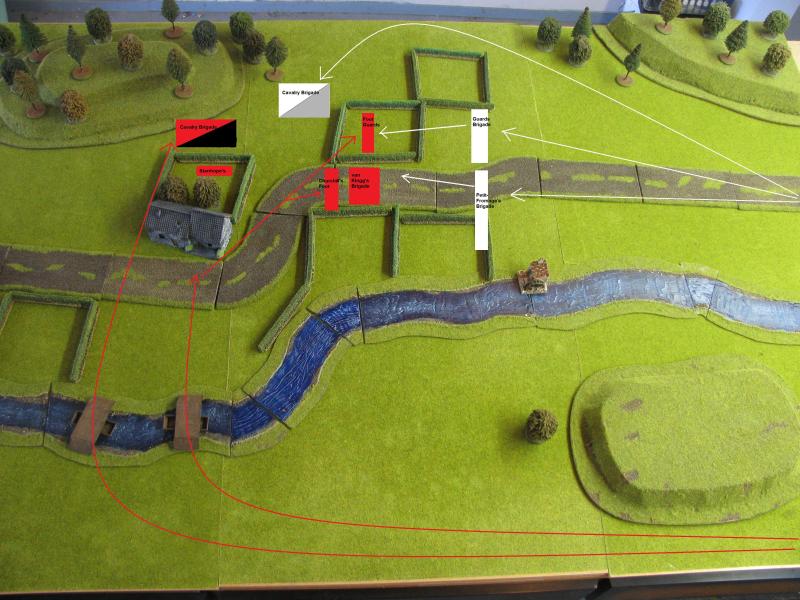

No artists were present at the battle, it being far too hurried an affair for any lazy bohemian to keep up, and it would be insulting to publish here any of the wildly inaccurate engravings that were produced in later years. Instead, the author has walked the ground and found it remarkably unchanged. Upon a satellite map he has indicated the general movements of the troops as best as he can make out.

Although the epic cavalry clash on the Left wing of the Allied position was technically a victory for the Maritime powers, the ability of Fois-Gras to marshal the Gendarmerie, reposition it in his centre, and help batter his way through Lord Maykitt’s English brigade proved vital. After a hard fought encounter, the French opened the road to Frankenberg and escaped.

Noteworthy was the defeat of the Gardes Francaises, after an appallingly disordered advance they received a volley point blank and broke to the rear. The First Foot Guards was the regiment responsible, and the meeting of the guards at Rheineck is a renowned moment in the Wurst war, and indeed in the whole of the wars of the Spanish Succession.

Of all the Allied foot regiments in battle, Churchill’s foot was the most important, continuing to attack even as the rest of the Allied army withdrew to defensive positions at the pontoon bridgehead.

As night fell, the Allies attempted to reorganise their battered army around the bridgehead, but it was in too parlous a state to renew the offensive as the French army manning the lines at Rheineck slipped east, covered by the Gendarmerie, full of fighting fettle following their splendid battlefield performance.

Having won the strategic victory of forcing the lines of Rheineck, Pritzwalk retired to his tent to imbibe some schnapps and prepare his next move. Fois-Gras, hurting from being outmanouevred but pleased that his small force had acquitted itself so well twice in the space of a fortnight, sipped brandy and contemplated the map for his next move. At 2am he was reached by a rider with good news – reinforcements had entered the Archbishopric!

No comments:

Post a Comment